Recognizing Acquired HO

Early identification and proactive intervention can help patients

Screening for acquired HO is critical in cases of hypothalamic injury

Many patients may not be aware of acquired hypothalamic obesity (HO) as a risk following hypothalamic injury or may only be focused on other post-treatment concerns.1

Talk to your patients about signs and symptoms.

Clinical Diagnosis2-7

A clinical diagnosis of acquired HO is characterized by weight gain following hypothalamic injury, typically beginning within 6 to 12 months post-injury.

Variable Presentation3,8

Weight gain may be accelerated and/or sustained, and onset and progression can vary based on the type, location, and extent of hypothalamic injury.

Confounding Factors9

Recognizing acquired HO may be confounded by temporary weight gain from medications or hormone replacements.

Identifying acquired HO

Screen all patients with a history of hypothalamic injury due to3,10–13:

- Hypothalamic-pituitary tumors

- Tumor treatment

- Traumatic brain injuries

- Hypothalamic inflammation

- Stroke

Early signs and symptoms that can help identify patients with acquired HO include3,10–12:

- Sleep disruptions

- Fatigue

- Decreased physical activity

- Increased hunger or hyperphagia

In your patients with obesity, screen for any history of hypothalamic injury and other key features, which may include2,3,14:

- Signs of hypothalamic dysfunction

- Signs and symptoms of acquired HO

- Obesity that may have been resistant to traditional weight loss management strategies

Make a decisive diagnosis. Find resources and get more information.

Managing acquired HO

Diet

Exercise

Anti-obesity medications

Bariatric surgery

There is a critical need to recognize the urgency to diagnose and manage acquired HO due to its impact on patients and families.2,7,10,15–17

Patients may experience short-term weight loss with:

- Lifestyle modifications

- Anti-obesity medications

- Surgery

However, these approaches have shown limited efficacy in producing sustained results in acquired HO.2–7,18

While acquired HO can be challenging to manage, early identification and proactive intervention may help to slow the progression of weight gain and help patients better understand their disease.2,7,13,19

Join a searchable directory of healthcare professionals who treat acquired HO. Register Here

Currently there is no FDA-approved treatment specifically indicated for acquired HO.1,7,9

Disease education support for acquired HO

Many patients may be unprepared for the impact of acquired HO. Accessing tailored informational resources and one-on-one disease education can make a meaningful difference.

Acquired HO Resources

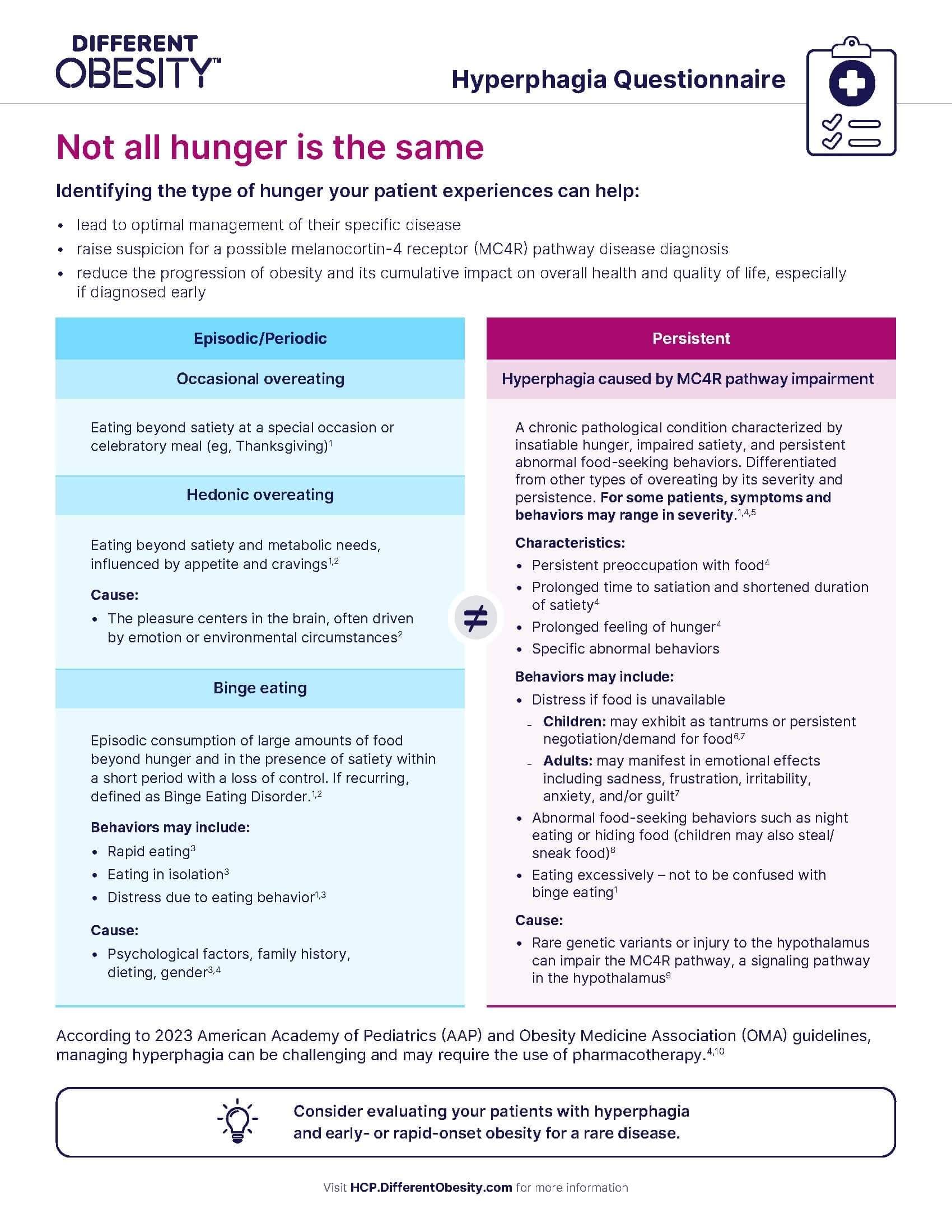

Hyperphagia Questionnaire

Identify hyperphagia in your patients with hypothalamic dysfunction

Acquired HO Brochure

Use this resource for an in-depth understanding of acquired HO

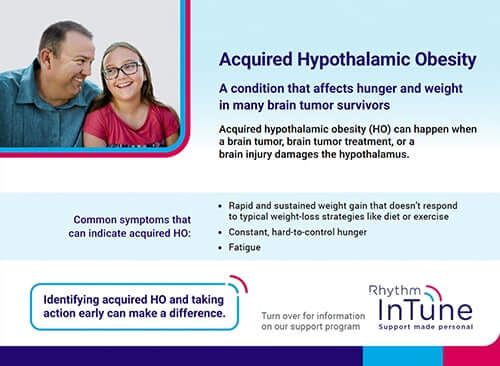

To learn more about the mechanism of disease, click here.Acquired HO Rhythm InTune Patient Disease Education Handout

Share this handout with patients to inform them about personalized one-on-one disease education support

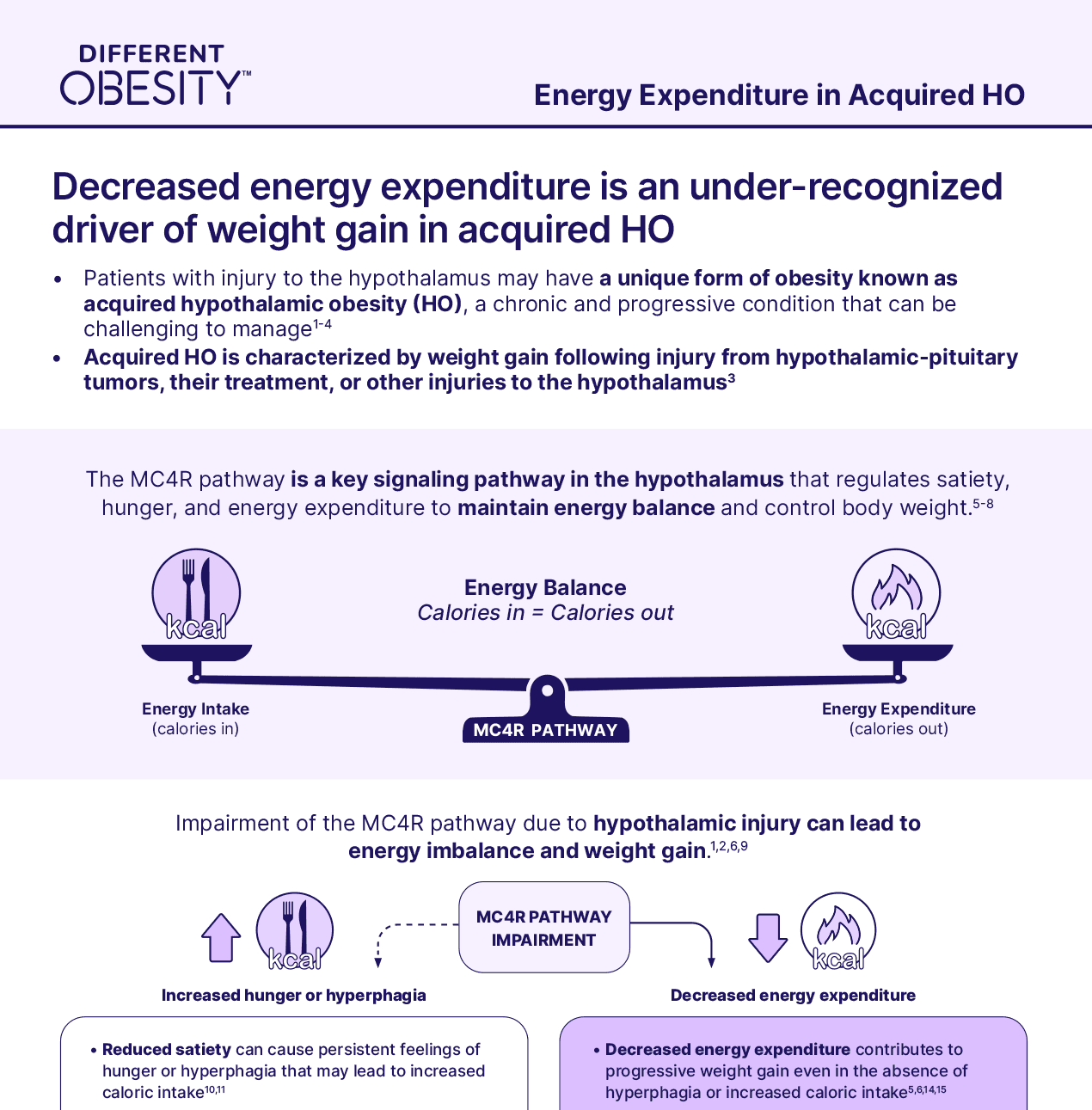

Energy Expenditure in Acquired HO Overview

Review this resource to better understand the role that energy expenditure plays in acquired HO

Join the HCP Directory

Be included in our list of healthcare providers who manage patients with rare diseases that cause obesity

Sign up to receive disease education resources for your patients and practice, as well as the latest updates about acquired HO.

Personalized one-on-one disease education support* for your patients living with acquired HO

Rhythm InTune provides disease education resources, wellness tips, and connection to a community for people living with acquired HO

Patient Education Managers are employees of Rhythm Pharmaceuticals and do not provide medical care or advice. We encourage patients to always speak to their healthcare providers regarding their medical care.