Hyperphagia and Obesity

The physical and emotional burden of hyperphagia and obesity

Acquired HO carries significant, long-term burden1,2

Acquired HO is associated with decreased quality of life and increased burden for patients and caregivers.2,3

Acquired HO can result in:

Physical burden2,3

Significant burden on the day-to-day lives of patients, who may experience:

- Sleep disruptions

- Fatigue

- Decreased physical activity

- Increased hunger or hyperphagia

- Weight gain, even in the absence of increased caloric intake

Emotional burden2,3

Distressing emotional and social challenges for patients:

- Frustration due to difficulty losing weight

- Poor body image perceptions

- Fewer positive social interactions

- Negative impact on mental health

Burden of hyperphagia

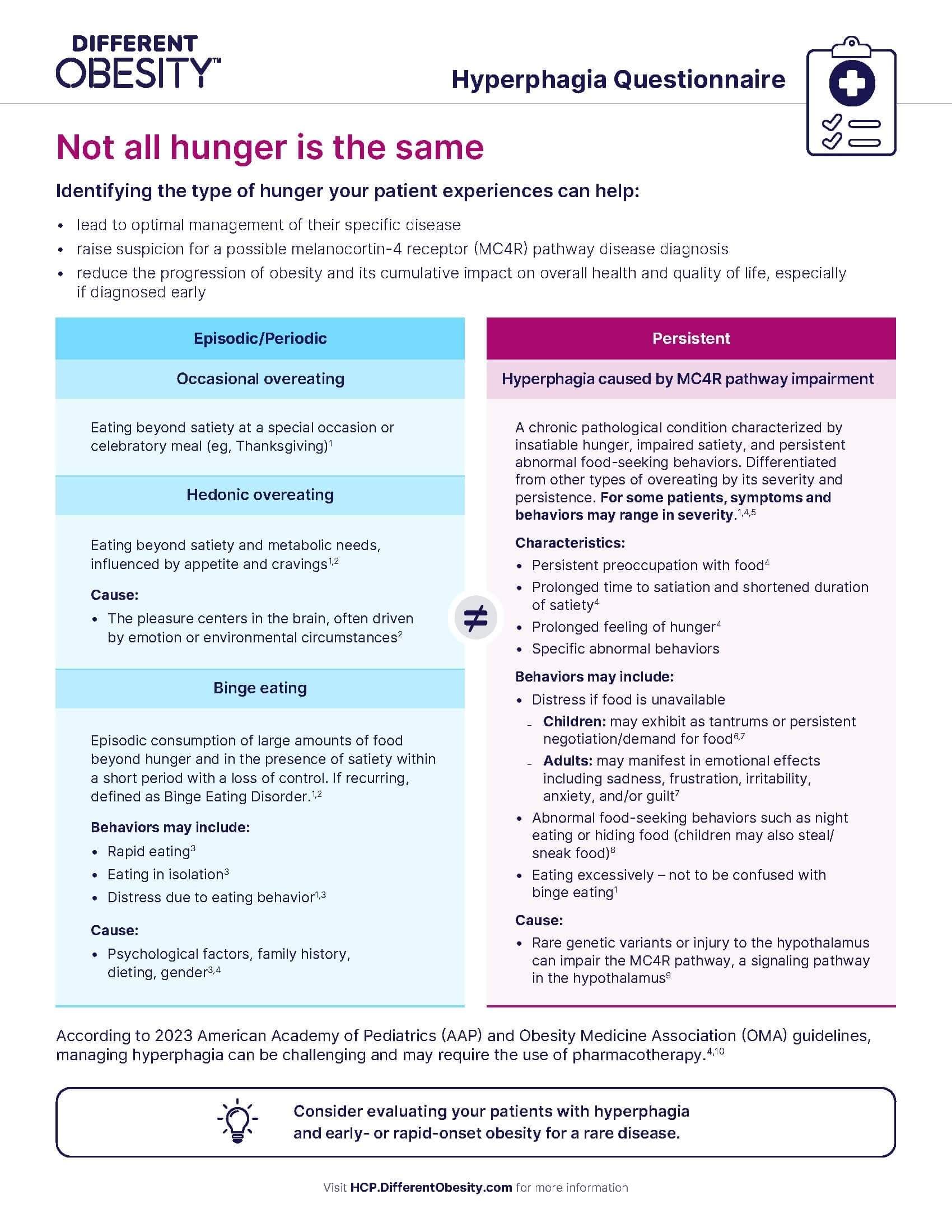

Hyperphagia is a chronic pathological condition characterized by insatiable hunger, impaired satiety, and persistent abnormal food-seeking behaviors. It is differentiated from other hunger associated with overeating by its severity and persistence.4

Hyperphagia contributes significantly to patient and caregiver burden in acquired HO2,5

Mean Burden Scores (ZBI) Reported by Caregivers of Craniopharyngioma Patients3,*

30.3

For Caregivers of Patients without hyperphagia (SD: 16.7, n=38)

41.1

For Caregivers of Patients with hyperphagia (SD: 12.8, n=44)

For reference, ZBI scores of

23.7 for cancer caregivers and 36.8 for Alzheimer's disease

caregivers have been reported6

23.7

36.8

ZBI score

*Based on 82 self-identified caregivers of hypothalamic-pituitary brain tumor survivors responding in an online survey to the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI), which assesses the perceived burden experienced by caregivers of individuals with chronic illnesses or disabilities; a higher score indicates a greater level of caregiver burden.3

Around 70% of patients with acquired HO experience hyperphagia, though the presentation of symptoms and behaviors can vary in severity.3,7

“Food ruled my life and still does to a certain degree…it’s a lot of grief and struggle in my everyday life.”

– Individual living with acquired HO

Downloadable

Identify hyperphagia in your patients with hypothalamic dysfunction.

Burden of obesity

Acquired HO is a major risk factor for related morbidity and mortality1,8

Long-term Effects of Obesity-related Sequelae in Craniopharyngioma Survivors9-11

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

Sleep apnea

Dyslipidemia

Hypertension

Glycemic disturbance

Cardiovascular disease