Acquired hypothalamic obesity

Acquired HO

Actor portrayal

Acquired hypothalamic obesity (HO) is characterized by hypothalamic injury leading to weight gain1-4

Healthy Hypothalamus5,6

The hypothalamus plays a key role in many diverse functions, including regulating:

Satiety and hunger

Energy expenditure

Body weight

Patients with hypothalamic dysfunction due to injury experience a variety of health concerns, one of which is acquired HO.5,6

Acquired Hypothalamic Obesity5,6

Unlike general obesity, acquired HO is characterized by distinct factors that can contribute to weight gain:

Hyperphagia

Decreased energy expenditure

Weight gain

Differences in type, location, and extent of hypothalamic injury may result in variable time to onset and progression of weight gain.5,7

While HO can be congenital or acquired, more than 80% of cases are acquired.8

Learn more about energy expenditure in acquired HO.

Questions about acquired hypothalamic obesity?

Causes of acquired HO

Known Common Causes8:

- Hypothalamic-pituitary tumors, including craniopharyngioma, astrocytoma, and pituitary adenomas

- Tumor treatment, including surgical resection and radiotherapy

Other Causes8:

- Traumatic brain injury

- Hypothalamic inflammation

- Stroke

Know who is at risk—acquired HO occurs in up to 75% of patients with craniopharyngioma following treatment.9

Mechanism of disease

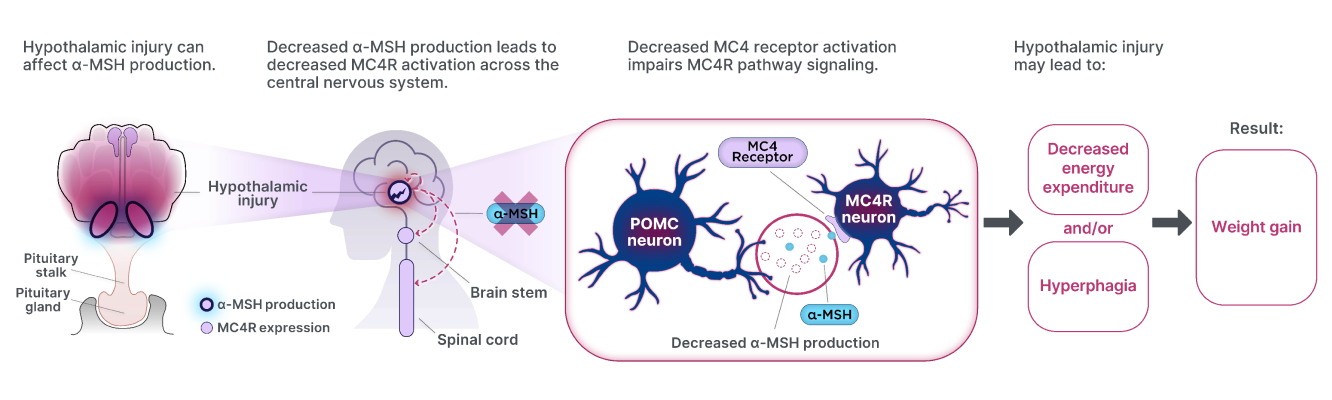

Acquired HO has an underlying pathophysiology that distinguishes it from general obesity.1,2,4

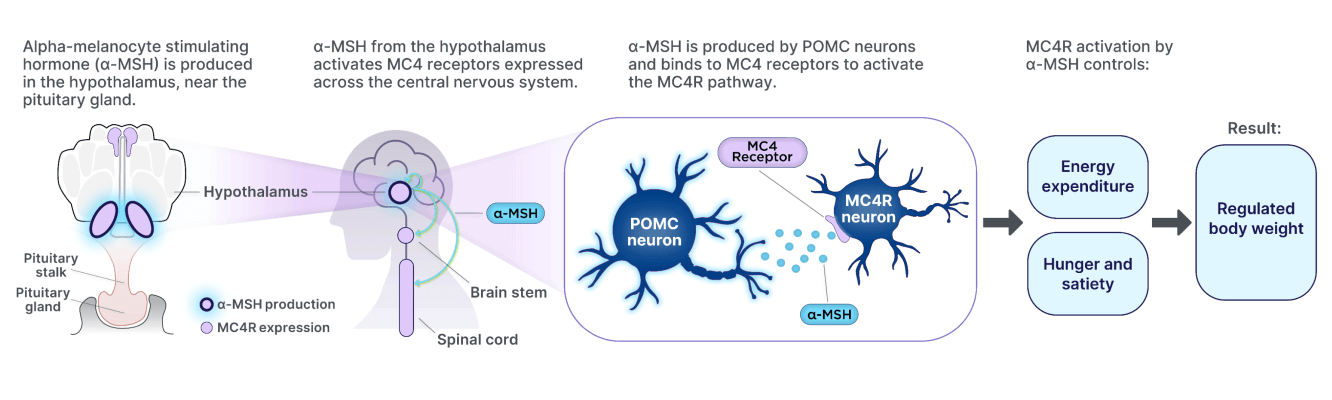

The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) pathway regulates energy balance and weight.10–12

Injury to the hypothalamus can disrupt MC4R pathway signaling, ultimately leading to weight gain.1,2,4

POMC=Proopiomelanocortin